by Jennifer Krebs | Mar 21, 2019 | Books

Ghost Wall, by Sarah Moss. On Maureen Corrigan’s review, I began Ghost Wall, a story of a teenager and her family joining an academic “experimental archeology” field course in the North of England. Wikipedia describes Experimental Archeology as “a field of study which attempts to generate and test archaeological hypotheses, usually by replicating or approximating the feasibility of ancient cultures performing various tasks or feats…Living history and historical reenactment, which are generally undertaken as a hobby, are the non archaeological person’s version of this academic discipline.”

Ghost Wall = pre-historical re-enactors (with a right-wing nationalist cast) + 2nd rate academic with lacky grad students + teen girl coming of age.

As the story unfolds, the protagonist’s father shows himself to be as brutal as the prehistoric Brits he emulates, and the protagonist, who loves her father, has to come to grips with what that brutality means to her.

by Jennifer Krebs | Mar 21, 2019 | Books

Blood, Water, Paint, by Joy Mccullough. I picked up this book because it was about Artemesia Gentileschi & I thought I’d be re-reading a book that I read a decade ago about her. No, that book,The Passion of Artemesia, by Susan Vreeland, had a different span and scope.

Blood, Water, Paint covers Artemesia’s late adolescence shortly after the death of her mother. Artemesia’s lonely, in a house full of boys and men, and her only real engagement is with the paintings that she does under her father’s name. As the book progresses, she is raped by an artist, and wishes him to be punished. In 17th Century Italy, however, it is mainly she that is punished. The book is a quick read about the injustices and lonelinesses of adolescence. One leaves the book wondering if art will save Artemesia.

The Vreeland book follows Artemesia throughout her life and provides different perspectives on her relationships with her family, and the art world of the 17th Century, and the legacy of her rape throughout her life. I think I’ll read it again.

In the meantime, should you visit Mexico City Soumaya Museum, you’ll find 3 canvasses of Artemesia’s. She is definitely looking to the heavens for answers.

by Jennifer Krebs | Mar 21, 2019 | Books

Happy Spring Solstice! The full moon was huge this morning. Ozzie and I had a lovely walk. I’ve been reading (which is mainly listening to audio books as I walk Ozzie) but my “writing time” has largely been “work time” or “entertaining time” or “traveling time.” As my goal for 2019 is to record all I read on this blog, I’m going to try to catch up in one post.

Asymmetry, by Lisa Halliday. An amazing book In three distinct parts. The first part is a story of a relationship between a 20-something young woman and a 70-something old man at different points in their love lives and writing careers. What stands out is that there doesn’t seem to be a discomfiting power imbalance between the two of them. Published in 2018 and not centered on me-too. They joke, they eat, have sex, write, watch baseball, struggle with their various issues independently and together. Halliday is witty and sensitive to both of them. In section #2, an Iraqi-American man is held in limbo in Heathrow Airport while the British customs agents try to figure out if he might be a terrorist, or a terrorist-to-be. This character, too, is sensitive and reflects on politics, his life choices to date, and his family. Section 3 features the 70-something writer, this time being interviewed a British radio station. While some book reviewers found this coda the best part of the book, for me the best part of it was a compilation of musical pieces purportedly the character’s choices. Not so much deep or haunting, but engaging. Halliday’s next will definitely be on my list.

by Jennifer Krebs | Feb 12, 2019 | Books

Kathryn Harrison has been on my “to read” list for years. Glad I picked up this slim volume (quick audiobook). Among her ancestors were Jewish merchants from Baghdad who became British citizens and then Americans. Some of her relatives peddled opium in pre-Communist China; others wrote poetry; some were hardly noticed. Young Kathryn attended Christian Science Church and Catholic school and spent much more time with her grandparents than the mother she resented, a bisexual spendthrift/ shoe collector. Riches to rags in 1970s LA as Kathryn gains consciousness of the world.

by Jennifer Krebs | Feb 12, 2019 | Books

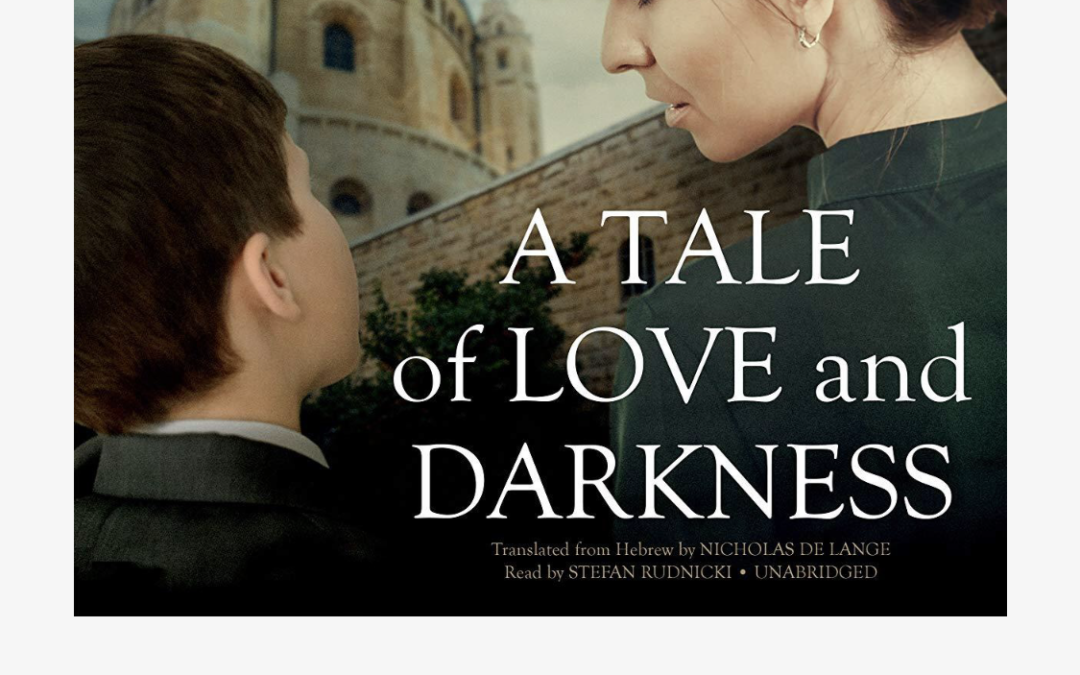

Amos Oz’s memoir starts in pre-independence Jerusalem and ebbs and flows back to Oz’s parents birth countries in Eastern Europe and Russia. Nu, what? Is is Oz’s grandfather’s standard greeting. He’s deeply skeptical of the socialist bent of Zionist, as he worries that they’ll bring Stalin to Israel. He is interested in traditional Judaism though hardly profoundly religious. He calls Menachem Begin’s argument style straight out of the Yeshiva – that he’ll just cast out his arguments and all will follow. (NOT!) Oz’s mother commits suicide when he’s still quite young and he and his father grow estranged. He leaves Jerusalem for Kibbutz Hulda where he exchanges his last name, Klausner, for Oz.

Oz is an expert at bringing even less important characters to life though his father offers a critique of an early book that Oz’s characters are more like caricatures. Ah, families!

by Jennifer Krebs | Feb 4, 2019 | Books, Uncategorized

N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth Trilogy

N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth Trilogy

I probably read this trilogy over the course of six months as I waited for each (popular!) audiobook to become available from the library. I remember listening to some of it walking through the park; another section by the S.F. Bay, and yesterday lying in bed while the rain pounded down.

A three word, plot synopsis of the trilogy would be “ashes to ashes,” for a whole variety of human and non-human creatures living in on a dystopian planet earth. The book starts with changes in a planet – to the atmosphere, to the climate, and to the actual substance of the earth. Although the time scale of the books is a bit confusing – weeks, decades, aeons shifting within 100 pages – the characters in the book are dealing with planetary changes as much as human-based dynamics.

This science fiction is really social critique, taking on class/caste issues, race issues, and gender issues. I’m not often drawn to SciFi because the make believe (hokey) names of people and things often put me off. This series, however, borrows heavily from geologic terms. I found it fairly easy to follow. Further, the struggles between people/castes/societies rang true: people oppressed because of intrinsic differences; people’s abilities unseen, discounted, or feared; and people’s lives diminished due to societal dysfunction.